Amigos de Brian 🇵🇪 🇪🇨

I’m currently writing this from home as I take a two week break to visit my family. Since my last writing I continued on the Peru Great Divide trail but decided to quit that in favor of easier, more populated areas to the east of the mountains. I lost my tent poles which hit me pretty hard, I cycled toward the ocean, and then I continued into Ecuador and had to rush a bit to reach Quito in time for my flight.

For another week or so I cycled with the same Brazilian cyclist with whom I’d spent the past month. That time has been quite good for learning Spanish because it’s the only language we have in common. I wonder if it’s taught me a skewed Portuguese-Spanish hybrid, only time will tell. We pedaled out of Huancavelica and immediately got on some incredibly steep climbs. This would be the standard for the next few days; the rolling hills of the high plateaus were a welcome respite after long, steep uphills.

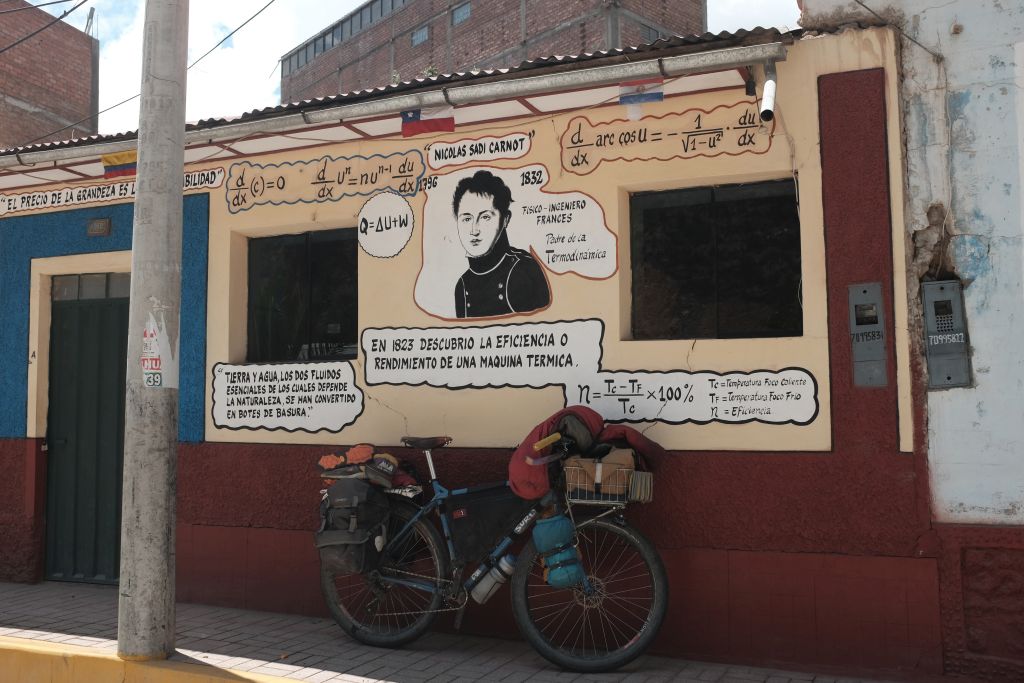

I could use some Carnot cycle right about now

Looking back on a nice climb

Some first turns on the Peru Great Divide trail

When starting the trail we were a bit worried about the onset of the rainy season in Peru and these worries proved to be well founded. Every day around two in the afternoon we’d begin searching for a shelter for the night before heavy, heavy rain and hail set in. One night this was a farmer’s sheep shed, another night it was out front of the local municipal office, and another it was in a local community center. People were always willing to give us a roof to sleep under to avoid the late afternoon downpours. In the town of Acobambilla we stopped early and went for a swim in the river. I had a good conversation with a lady and asked her why it seemed as though people were afraid of me. Her insights shed some light on why I had felt so unwelcome in certain rural parts of Peru. She shared with us that people are afraid that foreigners are going to kidnap their children, some of whom were also swimming in the river near us. After about an hour of chatting she gave us some oranges and we went to look for a roof to sleep under.

It's looking like rain...

...we're definitely climbing into a storm

A nice view up and over the pass

We had stopped early in Acobambilla because at the edge of town begins a long, sustained, and steep climb up to about 5,000 meters. After spending most of the morning and early afternoon reaching the top it began to rain. Luckily there was a small homestead at the top of the climb where we took shelter. We were tired and the lady who lived there said we could pass the night in the barn with some ducks and a four day old puppy. I had gotten caught out in the rain and felt pretty cold so I immediately ate something warm and got into my sleeping bag to shiver a bit and take a nap. When I awoke, I wasn’t sure if it was still the same day or the next, Ferdi whom I had cycled with earlier was also there now, and I felt quite nauseous and sick. I’m not sure what it was; probably a combination of altitude and having eaten something bad. I decided this was as far as I was going to go on the Peru Great Divide trail. It was too steep, too rugged, and too remote when in all honesty my favorite experiences are found when cycling through developed areas and taking in the liveliness surrounding me; I also enjoy making funny faces at staring children. I turned around toward Huancayo while Ferdi and Keke continued on the trail; from here I’d ride solo the rest of the way to Quito. The climb that had taken several hours the day before took about twenty minutes to descend.

Looking back at the homestead that fed us

Another nice downhill

Hiding from the rain with the turkeys

Approaching Acobambilla

The high point for me on the Peru Great Divide trail; the duck barn puppy campsite

I once again reached Acobambilla and found a colectivo bus there to take me to Huancayo. The bus was pretty full so I had to sit on the floor. I got even more sick and threw up on the bumpy, winding way back down into the valley. Eventually, the bus emptied out and I found a seat in the front. The driver woke me up when we reached Huancayo, I was the last one on-board. I got out, loaded up my bike, and reflected on my current state. I smelled bad, I felt bad, and I probably didn’t look my best. Now looking and feeling homeless, I thought, “this is where I’m at now, this is my life.” I found the closest hospedaje, which was run by a friendly young kid, checked in, took a shower, and went back to bed.

A church and some alpacas

Looking back on the stretch from Junín to Cerro de Pasco. It really reminded me of Tierra del Fuego. Beautiful!

When sleeping under a roof, protected from the rain, I like to not use my tent and simply lay out my sleeping bag and fall asleep. Camping in this way for about two weeks meant that I never used my tent. It was around this time while travelling between Huancayo and Junín and Cerro de Pasco that I noticed that I was missing my tent poles. Panic set in and the next day I decided to cycle back along the dirt road that I rode between Cerro de Pasco and Junín. Maybe they’d bounced off while riding the bumpy road. I didn’t find them and took a bus back to Cerro de Pasco that night. I was pretty upset about having lost the tent poles and while in my deepest mental dip so far on this long trip, the loss hit me pretty hard. I spent the next day trying to figure out where I’d lost them and contacting some places where I’d stayed. There was another cyclist friend a few days behind me and he very kindly and meticulously checked all of the barns and sheds I’d slept in. Unfortunately, my searching turned up nothing and I had to cut my losses and continue.

My bike on the roof of the colectivo

Beans drying

Without a tent, I now had to be more strategic about my choice of route; I’d need to find a town every 50-100 kilometers for either a hospedaje or at the very least a roof to sleep under. I’d be flying to the United States from Quito in about a month and could arrange for a new set of tent poles once I got there. The stretches that were too large to cross and which didn’t have any towns in between I’d have to cross by colectivo bus. I welcomed the change of pace and seeing Peru in a new way. Customarily, the drivers in Peru honk their horns when driving through a narrow, blind turn to warn approaching drivers. Sometimes, though the music is so loud in the van that the driver wouldn’t be able to hear an approaching car also honking, I wondered about this to myself but didn’t ask. When the music wasn’t too loud, I enjoyed chatting with the other people in the car and learning a bit more about them; it’s funny how some of my nicest conversations were while driving and not while cycling. One stretch of road under construction was so poor that it took us about eight hours to cover a bit more than 100 kilometers as we bounced and wound our way through the steep mountains.

Riding through Cañón del Pato down to the coast

Starting down Cañón del Pato

Tunnel after tunnel

The town of Huallanca. I had the best plate of lomo saltado here.

After a few days of cycling and crossing the Andes one more time, I reached the town of Huaraz and took a bed in a nice hostel for a few days. The town and its surrounding mountains are quite a tourist attraction and I was happy to speak English again for a few days and spend time with several English travelers. The few days that I was in Huaraz I ate at the same pizza place each evening; it was excellent. After some rest days in town I cycled the nice downhill stretch to Caraz in a single day. From there I planned to ride down the Cañón del Pato toward the ocean. This meant over 3,000 meters of descending over the next few days.

The canyon that keeps on giving

More and more tunnels

Riding out of yet another tunnel

As beautiful as it was, the cycling was still quite tough on account of strong headwinds coming up the valley. I had expected the downhill cycling to make for a few easy days but found that once the afternoon winds picked up it was tough pedaling, even for a downhill. The entire route was cut into the steep walls of the valley and eventually opened up to a broad river basin. I didn’t meet many other people along the route and didn’t see much traffic; they were quiet days. Every now and then I came across a town with a small restaurant or shop. After stopping for a snack and chatting with the owner they were always very welcoming and allowed me to pass the night under a roof or in a small, spare room that they had available.

Starting to wonder who built this road and why

The canyon opening up into a broad river valley

Flatter and more pedaling

I pedaled through the wind and rode the rest of the way down to the coast and the town of Chimbote. There I met up with a Swiss traveler whom I’d met the year before over breakfast in a small Indian town. Then, we’d talked about the potential for taking this trip, how great it would be, but how risky it felt to get started; he encouraged me to go for it. Now, I was out here and doing it. We’d kept in touch while one of us went around the globe toward the east and the other came from the west. As I was riding into the city I saw a sign for Chimbote, a town known for its fishing industry and its steel mills. It sure smelled like it. There wasn’t much reason to visit Chimbote aside from being the place where it so happened that our paths would cross once again. We had some lunch, some coffee, caught up, and then continued on our respective trips.

It sure was pretty, though!

Another picture of my bike seeing the world

The valley floor

From Chimbote I’d have to take a bus to northern Peru if I was to catch my flight from Quito, so I took a night bus to the border town of Tumbes. To get my bike on the bus I had to package it, so I went to some local bike shops to find a large enough box and then I returned to the bus station. After watching me struggle for a few minutes to get everything packed, a few guys helped out, one of whom turned out to be the bus driver himself. I boarded the night-bus and arrived in Tumbes early afternoon the following day. Tumbes is the last major Peruvian city on the coastal road toward Ecuador. Riding the bike for so long, you get used to a slower rate of change in your environment. So you experience quite a sudden and jarring change after such a long bus ride. A kind Venezuelan man assisted me as I unboxed and rebuilt my bicycle. I got a room at a hospedaje in the busy little city and got some food. The next day, I exchanged my last Peruvian Soles for US Dollars and rode into Ecuador.

We'll cross that bridge when we get there

The first signage I've seen indicating a pan-American route

Entering Ecuador

I entered Ecuador at the coast and planned to cycle back into the mountains toward the city of Cuenca. From other cyclists I had heard some real horror stories about Ecuador but my experience so far has been one of a very friendly, open, and welcoming country. On my second day in Ecuador I cycled about 100 kilometers on a very slight uphill and saw nothing but banana plantations the entire day. Every so many kilometers someone would wave me down and hand me a bag of bananas or stalks of guaba; I had enough fruit to last me several days.

Crossing the bridge into Ecuador

A straight stretch of road with nothing but bananas on both sides

Cacao beans drying

In Ecuador I quickly got the impression that this country is much closer within the sphere-of-influence of the United States. Not only do they officially use the US Dollar as their currency but people talked and asked about the United States much more than I had previously experienced further south. Whoever I spoke with had questions or comments for me. Why is it so hard to get in? Why did my husband get deported? My cousin or son or uncle works there. I thought the sudden and stark change was noteworthy.

Sunset from my camp with more bananas

A two dog standoff in Guamote

A Lada 2105

The climb from sea-level back up to 3,000 meters took me a few days of slow but steady climbing. I was very impressed with the city of Cuenca. At first I thought I had possibly entered through the rich neighborhood but was pleasantly surprised to find that the entire city is quite nice and seems very livable. I stayed for a rest day and enjoyed the festivities surrounding a holiday weekend celebrating Día de los Difuntos and the city’s independence day. From there, in a bit of a rush to reach Quito, I pedaled along the main road past other nice little towns like Alausí and Baños de Agua Santa. I took another rest day in Baños where I visited a waterfall and one of the town’s many thermal baths. Together with some Ecuadorean and English travelers we did plenty of cycles from the cold pool to the very hot thermal bath. The first night in town was the last Saturday of the holiday weekend, which made it quite difficult to find a place to sleep without a reservation. Eventually I found a bed and the following day the town was considerably quieter as most people had gone home.

A wonderful stretch in Cotopaxi National Park

Starting downhill toward Quito

After Baños I made it to Latacunga where I spent the night and then left the main road one last time to cycle through Cotopaxi National Park. The highlight of the park is the Cotopaxi volcano, which should have been visible for the past day or so but was completely covered in clouds while I was there. There was a nice campsite in the park where I, without tent, could sleep in the covered picnic area. Coincidentally, I ran into the French couple with whom I’d cycled in Bolivia a few months earlier and we had dinner together. I woke up around sunrise the next day hoping to catch a glimpse of the volcano but it was very foggy. I had a slow morning hoping the weather would change and knowing that the rest of the way to Quito was mostly downhill. I decided to just let the mountain do its thing, aired down my tires, and started the big downhill toward Quito on a nicely flowing gravel road with a strong tailwind. It was a great stretch of road.

Over the course of three days, the Cotopaxi summit was visible for about five minutes

Tired and starting the final descent into downtown Quito

In all honesty, I was afraid of coming home for these two weeks while I was in my mental dip in Peru. It was the worst I’d felt so far on the trip and I thought that if I left then that I’d just quit the whole trip. I’d planned to leave my bike in Quito as a type of anchor just to be sure. But my time cycling in Ecuador and chatting with the many friendly people has left me feeling excited and re-energized. As a result, my perspective on a two week break completely changed. On the late night drive to the airport I had a remarkably coherent conversation with the cab driver Gonzalo; I was excited to go see my family but I was also excited to continue my trip. In these past few days, somewhere after Alausí, I rolled through my 10,000th kilometer on the bike. I’ve now been cycling for ten months and I’m wondering what another ten would look like. I find myself thinking of the road ahead and feeling the excitement of visiting Colombia and Central America, of riding through Mexico, and then along the west coast of the United States. Wouldn’t that be cool?